SAVE at 50: celebrating half a century of campaigning

At a time of housing and climate crisis, much of SAVE’s work shows property owners, developers and local authorities that historic buildings can be restored and reused.

|

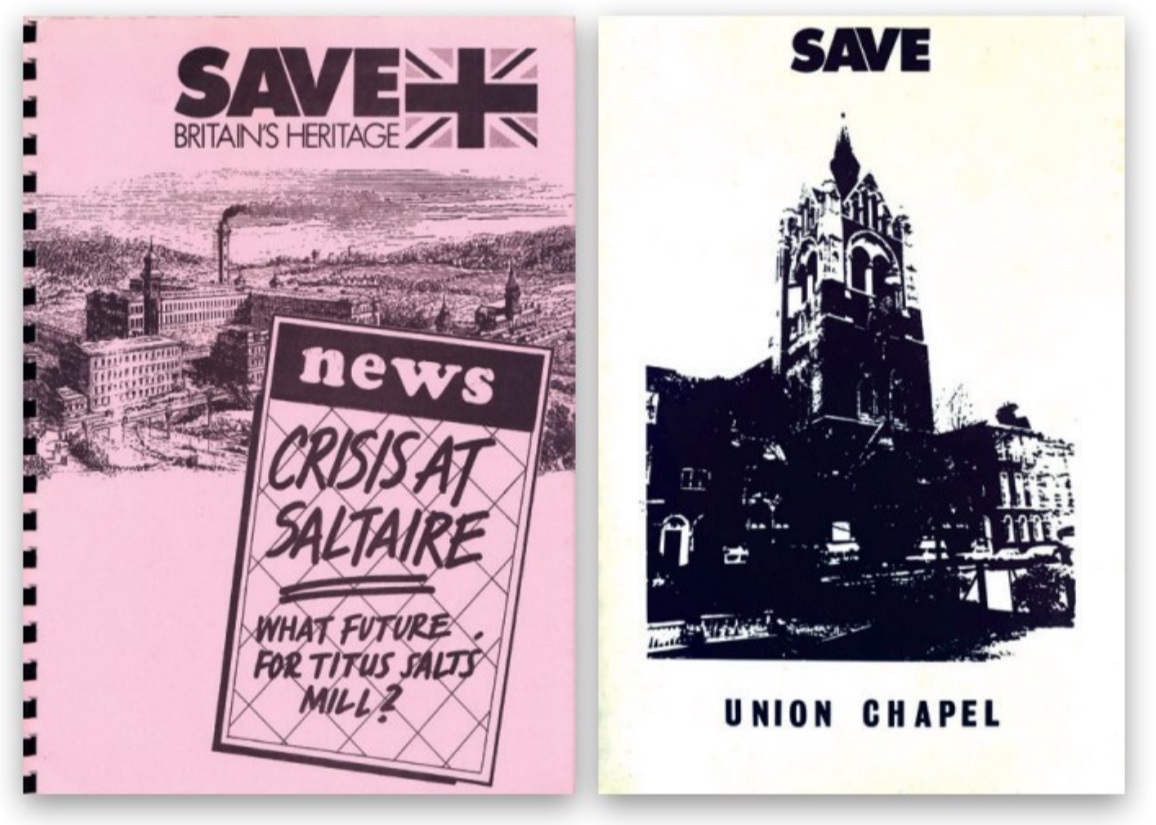

| In 1986 SAVE proposed that the vast Saltaire mill might accommodate a museum, homes and light industry. This 1982 pamphlet suggested Union Chapel’s potential for use as a performance space. |

Contents |

Introduction

In the first eleven weeks of 1975 – European Architectural Heritage Year – local planning authorities received almost 500 applications to demolish historic buildings, 334 of which were statutorily listed. This statistic was produced by an organisation called SAVE Britain’s Heritage, then in its infancy. A coalition of journalists, architectural historians and planners, SAVE decided to fight back against this tide of demolition and dereliction.

Now in its fiftieth year, it is hard not to invoke David and Goliath when describing SAVE and its campaigns. SAVE takes on buildings great and small, refusing to discriminate based on designation. The small, fiercely independent charity has taken on its fair share of seemingly unassailable cases using the powerful combination of tactical press, legal action and alternative schemes, which contribute to SAVE’s unique campaigning style.

Early days

SAVE was founded following the success of the 1974 Destruction of the Country House exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum, commissioned by the museum’s then director Roy Strong and curated by SAVE’s founding chairman Marcus Binney, architectural historian John Harris and curator Peter Thornton. The exhibition generated strong support for conservation, with visitors invited to enter the Hall of Destruction, plastered with images of country houses lost to demolition.

SAVE led by example, buying Barlaston Hall for £1 in 1981. Derelict and in structural peril, the palladian country house stood diagonally across a geological fault line. SAVE set up an independent trust to complete the structural works at Barlaston, and by 1992 buyers were secured who would complete the refurbishment. At this time, SAVE began to work alongside architectural designer and property developer Kit Martin, who transformed Hazells Hall into 12 separate dwellings after SAVE and the Ancient Monuments Society halted its demolition at public inquiry. SAVE’s early work looked forward just as it looked back, ensuring that these buildings were brought back into meaningful use.

Campaigns to save country houses were followed in quick succession by those to save train stations, hospitals and mills. These buildings A visit to Barlaston Hall before restoration (Photo: Marcus Binney) Barlaston Hall restored (Photo: Peter I Vardy, Wikimedia) did not, in Binney’s words, have to be pensioners on the state, but ought to be brought back to life, serving the communities of which they were once an integral part.

In April 1986, SAVE declared a Crisis at Saltaire following the closure of Salt’s Mill and proposed that the vast Italianate textile mill – once the world’s largest building by floorspace – might accommodate a museum, homes and light industry. That month, SAVE organised a seminar in Saltaire, where politicians, museum officers, the public and those with experience converting mills, were invited to discuss the building’s future. In 2001, Saltaire was designated as a world heritage site, and Salt’s Mill now houses the largest collection of David Hockney’s art, as well as shops, restaurants and light industry. The sheer quantity of formerly industrial space continues to present enormous opportunity for development. In 2021, Historic England estimated that, if converted, approximately 2.3 million sq metres of unused floorspace in mills across northern England could provide around 42,000 homes.[1]

Alternative schemes have become a vital tool in SAVE’s armoury, used to prove a building’s capacity for sensitive regeneration. These schemes, produced with the aid of architects and structural engineers, are not simply speculative. In 1979, Marcus Binney proposed an art gallery at Bankside Power Station, and by 1992 the decision was made that Sir Giles Gilbert Scott’s mid-century behemoth should be converted into Tate Modern, now one of the world’s largest museums of modern and contemporary art. Similarly, when the Union Chapel in Islington was threatened with demolition in 1982, SAVE suggested ‘hiring out the chapel itself for musical performances’. In 1991, congregants established the chapel as a venue in order to fund its upkeep. Now one of London’s most-loved performance spaces and acknowledged as one of the best examples of nonconformist architecture of the nineteenth century, the Union Chapel has hosted names such as Amy Winehouse, Elton John and Adele, while still serving its active congregation.

Yet these schemes are also tools in their own right. When Smithfield General Market was under threat, SAVE initiated, fought and won two public inquiries alongside the Victorian Society. The first was in 2008 against the building’s total demolition, and the second in 2014 against a proposal that would have gutted its interiors and replaced the glass roof and magnificent dome with overbearing office blocks. SAVE’s commitment to raising the public profile of built heritage perhaps reached an all-time high during this campaign, when an image of SAVE’s ‘army’ of Lady Gaga lookalikes marching in defence of the market was reposted by the pop icon herself (her famous meat dress provided the perfect link to the battle for Britain’s finest wholesale meat market).

In 2012, SAVE commissioned architect John Burrell to design an alternative vision for Smithfield, submitted as a rival planning application. The secretary of state for communities and local government cited the economic viability of the SAVE/Victorian Society proposals as a key reason for the other scheme’s refusal, as they indicated that ‘such a regeneration scheme would be possible, viable and deliverable’. Here, the alternative may not have prophesied the market’s eventual use – the soon-to-be new home of the London Museum – but proved that Smithfield could continue serving the City as a public space, just as it has for almost 150 years.

Catalyst for positive change

SAVE’s focus on reuse not only fights for the future of the historic environment, but also the communities immersed within and defined by it. A campaign to stop over 400 Victorian houses – which constitute the Welsh Streets in Toxteth, Liverpool – being bulldozed saw SAVE and community campaigners square up to a true Goliath: the highly controversial 2002 Pathfinder policy which left 400,000 terraced houses in northern England at risk of being flattened. In 2011, on a mission to prove that the Welsh Streets’ houses made comfortable homes, SAVE bought, refurbished and let out 21 Madryn Street, the former home of Ringo Starr’s aunt.

Even after the withdrawal of the national Pathfinder programme, Liverpool City Council pressed ahead with demolition plans for the 10 streets. SAVE fought these proposals at public inquiry and ultimately won, saving these homes from the wrecking ball. The houses were restored as family homes by rental property developer Placefirst, with Historic England noting that the development ‘is attracting former residents to return and has been recognised as one of the “coolest” areas to live in the city’.[2] It is estimated that across England up to 670,000 new homes could be created through the repair and reuse of historic buildings. The Welsh Streets show how retention like this can create homes while strengthening local identity.[3]

SAVE brings heritage into the mainstream, recently leading new discussions regarding the environmental impact of knock-it-downand- rebuild schemes. In 2022, SAVE commissioned a report on the carbon cost of Marks and Spencer’s plans to demolish and rebuild its flagship Marble Arch store from sustainability and carbon emissions expert Simon Sturgis. The report’s findings – that comprehensive retrofit would produce substantially less embodied carbon emissions than demolition and building from scratch – triggered a hunt for radical new proposals for the building’s reuse. SAVE and the Architect’s Journal cohosted the Re:Store charette to generate ideas, asking entrants to prioritise whole-life carbon design principles while conserving the original 1929 building. SAVE’s campaign for Marks and Spencer was the first time that heritage arguments and those regarding the embodied carbon cost of demolition were jointly presented at public inquiry. This campaign attracted national media attention, generating interest well beyond the heritage sector and promoting the reuse of historic buildings as a core consideration in sustainable design.

The future of SAVE

Fifty years on, SAVE’s work is more relevant than ever. As local authority heritage budgets plummet, the planning system becomes more hostile and grants become ever scarcer, SAVE presents an alternative vision of what heritage-led growth could look like working with community groups to raise awareness about vulnerable buildings.

This means continuing to stand up against wasteful wrecking-ball schemes and encouraging sympathetic revival. At the time of writing (April 2025), SAVE has teamed up with other heritage bodies to re-form the Liverpool Street Station Campaign, defending the station from proposals which would overshadow it with an over-scaled office development and demolish its listed concourse. SAVE is also fighting proposals for the construction of a 17-storey office-led proposal in the Whitechapel High Street conservation area, challenging the government’s decision not to list an 18th-century mill in Manchester, and running a petition calling on the Scottish Parliament to help prevent the unnecessary use of emergency public safety powers to demolish listed buildings. As part of 50th anniversary celebrations, SAVE’s buildings at risk register – an ever-growing resource which highlights over 1,400 historic buildings whose future is uncertain – has been made free to access. SAVE is also hosting a programme of events across the UK to engage and equip communities to bring new life to their remarkable buildings.

The reuse of historic buildings has the potential to improve the outlook for two of the most significant crises facing the UK today: housing and climate. Much of SAVE’s work leads by example, showing property owners, developers and local authorities that retention and reuse is possible. Still a small organisation, SAVE continues to fight for the historic buildings that stand at the heart of our communities.

References

- [1] Historic England (2021) ‘Driving Northern growth through repurposing historic mills’.

- [2] Historic England (2021) ‘Design Case Study: Welsh streets Liverpool 8’.

- [3] Historic England (2025) New Homes from Vacant Historic Buildings.

This article originally appeared as ‘SAVE at 50: celebrating half a century of campaigning’ in the Institute of Historic Building Conservation’s (IHBC’s) Context 184, published in June 2025. It was written by Eve Blain, casework intern at SAVE Britain’s Heritage.

--Institute of Historic Building Conservation

Related articles on Designing Buildings Conservation.

IHBC NewsBlog

RICHeS Research Infrastructure offers ‘Full Access Fund Call’

RICHesS offers a ‘Help’ webinar on 11 March

Latest IHBC Issue of Context features Roofing

Articles range from slate to pitched roofs, and carbon impact to solar generation to roofscapes.

Three reasons not to demolish Edinburgh’s Argyle House

Should 'Edinburgh's ugliest building' be saved?

IHBC’s 2025 Parliamentary Briefing...from Crafts in Crisis to Rubbish Retrofit

IHBC launches research-led ‘5 Commitments to Help Heritage Skills in Conservation’

How RDSAP 10.2 impacts EPC assessments in traditional buildings

Energy performance certificates (EPCs) tell us how energy efficient our buildings are, but the way these certificates are generated has changed.

700-year-old church tower suspended 45ft

The London church is part of a 'never seen before feat of engineering'.

The historic Old War Office (OWO) has undergone a remarkable transformation

The Grade II* listed neo-Baroque landmark in central London is an example of adaptive reuse in architecture, where heritage meets modern sophistication.

West Midlands Heritage Careers Fair 2025

Join the West Midlands Historic Buildings Trust on 13 October 2025, from 10.00am.

Former carpark and shopping centre to be transformed into new homes

Transformation to be a UK first.

Canada is losing its churches…

Can communities afford to let that happen?